This article was written by my friend Stefano from X (@Stefano_1799).

The situation faced by Global Atomic is extremely delicate. The company finds itself suspended among three scenarios that it constantly swings between, as if it were a pendulum. The real possibility of obtaining financing for the Dasa project, potentially transforming it into the best opportunity across the entire #uranium-miner landscape. The risk of further delays in raising funds, which could force it once again onto the equity market to raise capital, with consequent additional dilution of shareholders and ever-increasing difficulty in raising capital. The failure to obtain the necessary financing within the required timeframe; an event that could force the company to slow down or even halt operations, finding itself in an extremely delicate situation similar to the one experienced by Orano, which ended with the closure of the mine and nationalization of the site. It is clear that the situation with Orano is closely related to Niger’s desire to distance the French power from its territory. Consequently, it is incorrect to think that similar measures would be applied in the event of problems with Global Atomic, since the historical and political context is different.

HOW GEOPOLITICS AND HISTORY HAVE SHAPED THE CURRENT URANIUM-MINING PATH IN NIGER

It is important to specify that the relations among the United States, Canada, and Niger are profoundly different compared to those between France and Niger.

Colonized by France in 1922, Niger endured decades of domination and exploitation, continuing even after independence in 1960 through control of its strategic resources. Uranium, discovered during the colonial era and exploited since 1971 by the French company COGEMA (later Areva, now Orano), fueled France’s nuclear program for decades, leaving the country only marginal benefits.

The July 2023 coup d’état in Niger found strong popular support, heavily fueled by the M62 movement (named for the year of independence of many African countries, founded in 2022) to denounce French interference and the exploitation of national resources.

The military junta took power in Niger, but it is often mistakenly assumed that only leaders make history and fully dictate a country’s political direction. In reality, even the most rigid dictatorships require a popular support base. Resentment toward France, a legacy of colonialism, remains an open wound in many African states, and today manifests in partially coordinated rebellion across several nations.

However, the junta’s takeover and policies leaning toward partial closure to the West do not mean that Niger is embarking on a path of complete isolationism. First, isolation has never worked historically; second, the web of global market interconnections and the entrenched presence of superpowers—United States, Russia, and China—make total closure unthinkable. Africa, and in particular Niger, is now a geopolitical battleground: who will control access to its resources?

This contest, ultimately, could also work in favor of the junta: according to a simple economic principle, the more bids

there are, the higher the price.

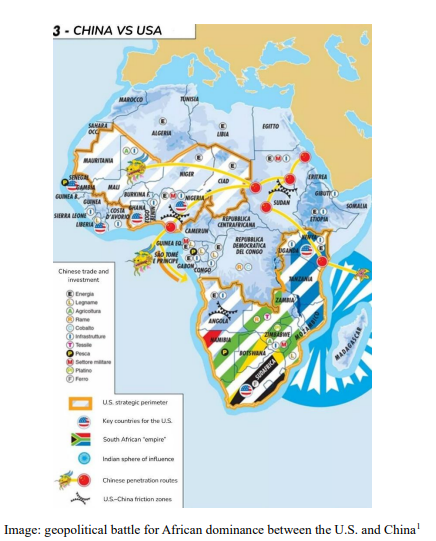

Look at front image.

This extremely explicit map, produced by the Italian geopolitical magazine “Limes”, clearly shows how Niger falls within the strategic perimeter of the United States. However, the events of the last three years have completely rewritten the balance of power in the region.

The yellow arrow passing through Niger shows how China, through the Belt and Road Initiative, is consolidating its presence in the country with significant investments in infrastructure, energy, and transport. A concrete example is the construction of the Zinder refinery and the related pipeline to the capital Niamey, which represents one of the key projects in the cooperation between the two countries.

At the same time, Russia is gaining ground as a military and political actor. Taking advantage of a growing wave of antiWestern sentiment, Moscow presents itself as a credible military alternative to France, which has declined after the end of Operation Barkhane. Popular support for collaboration with Russia has manifested openly in numerous demonstrations, where Russian flags have symbolically replaced French ones.

US STRATEGIC PUSH

The United States has fallen dramatically behind on the strategic front in Niger and must play its cards. After hitting the lowest point in bilateral relations—including the expulsion of the American military, closure of the embassy, and severance of diplomatic relations—a partial turnaround has occurred.

1

https://www.limesonline.com/carte/cina-vs-usa-14734651/

The United States has shown willingness to meet Niger’s requests, thus opening a channel of dialogue that has allowed rebuilding a closer relationship than in the recent past.

In this context, the US International Development Finance Corporation (DFC) could tilt the scales. It is now clear to the market how much Niger’s economy would benefit from successful development of the Dasa Project.

Currently 450 workers are employed, with a forecast to reach 900 in full production. The life-of-mine production plan projects output of 61.8 million pounds, with high probability of an upward revision. That revision could stem from conversion of 51.4 million pounds of “inferred” resources into “indicated” ones, and from potential expansions of the ore body.

The cash flow generated over the mine’s operational life could amount to USD 5 billion at current uranium prices, but this figure could double—exceeding USD 10 billion—if extractable resources increase or market prices rise, or most likely, both. For a country like Niger, this economic flow is highly significant, given that the government holds a 20%

stake in the project and also benefits from taxes and royalties under local mining code. It is therefore clear that financing from an American fund would project the United States into a dominant position in Niger’s future geopolitics.

Ideally, all this should occur within a democratic transition by 2030. And we know how rich American history is with episodes in which elections in foreign countries were influenced by its own interests. It is clear that one would need “hands in the game” to exercise control and influence in a country as complex as Niger, and the DFC would be the right vehicle to achieve that.

However, the situation remains uncertain. Unforeseen events could once again overturn current balances and hinder development plans. So far, one could say that everything that could go wrong has gone wrong. Therefore, it would not be surprising if this trend were to continue, given the high degree of unpredictability in the Nigerien context, particularly since the military junta took power.

Nevertheless, several investors assert that financing is now close, as the DFC has been working on the agreement for over two years. But the crucial question is: why, after all this time, has the financing still not been finalized?

INTERNAL AND EXTERNAL CHALLENGES FOR THE COMPANY, MANAGEMENT, AND INVESTORS

The obstacles standing in the way of successful funding and construction of the Dasa project are both endogenous—to Global Atomic—and exogenous, therefore outside the control of the company and consequently its investors. Contrary to some representations—including the official narrative of Steven Roman, attributing the last delays to mere

bureaucratic procedures—it is evident that substantial and complex obstacles have slowed or blocked the process. These obstacles are of two types: endogenous (within the company’s control) and exogenous (beyond it). Understanding this distinction is essential to accept that no investor can have total control over the outcome of this high-risk—but potentially highly profitable—bet.

Among the endogenous obstacles is the difficulty of communicating effectively with DFC partners and the joint-venture in order to build a solid relationship that leads to financing on reasonable terms and a cost of capital sustainable for the company, despite the undeniably risky context. Another extremely critical aspect is communication with investors: so far it has not been up to par. Investors need clarity, not illusions based on unrealistic timelines. Exemplary in this sense was the July 16, 2024 announcement in which Global Atomic communicated that the DFC’s credit-committee decision had been postponed to August 2024—a statement already made in the past and never realized.

One cannot rule out that the DFC may have provided incorrect timelines, but the company did little to correct course. It continued to sell hope, probably to stay afloat and survive. If upcoming communications are more honest—as in the last interview where Roman stated he “hopes” that approval arrives in Q3 2025—then new stock market crashes could be avoided each time truth hits investors.

Among external factors, regional political and geopolitical instability reigns supreme, as does the possibility of another regime change that could further destabilize the region and ruin institutional relations with Western states.

But the current and tangible critical issue is the border situation between Niger and Benin. This element represents a true critical node. As long as the border remains closed or a certain commercial export solution for the extracted material is not found, it will be very difficult for the DFC to approve a USD 260 million loan for a project that—though promising— would have no certainty of being able to export its product and thus generate revenue to repay the debt.

Roman mentioned alternative routes—such as the port of Lomé in Togo, or ports in Nigeria and Algeria—but none currently holds the Category 7 security certification for transporting radioactive materials. Only the port of Cotonou in Benin is currently compliant. Options via air or through other ports therefore remain uncertain, further increasing

perceived risk. The border closure has already caused deterioration of Orano’s financial situation—but that was a markedly different situation. It was the systematic refusal by the Nigerien junta to approve alternative export routes, even temporary ones, that ultimately backed Orano into a corner. The prolonged blockade, combined with absence of certified safe routes for uranium concentrate transport, made any logistical solution impossible. Suspension of activities and subsequent state takeover of the mine were thus not isolated events but the culmination of a strategic escalation that stripped Orano of any contractual leverage.

Global Atomic would thus be facing a different dynamic, and one hopes that the junta will at least partially accommodate the company’s needs—but one can be anything but certain of that. All these factors explain why the financing has not yet arrived. It is clear, therefore, that using the two years as justification for the delay in financing is not a solid or reasonable argument. Despite that, positive signs recently have aligned a series of factors, providing momentum to overcome the obstacles previously mentioned.

A TURNING POINT ON THE HORIZON?

DFC IMPACT

The impact that the project would have on Niger’s economy, the increase of American influence in the territory, and the growing global uranium deficit—estimated at approximately 1.5 billion pounds by 2050—are creating a favorable conjuncture; who will produce the much-needed pounds?

The “nuclear renaissance” is visible to all, but it will require massive supply increases that current prices cannot support. The market is rusty, frozen for years by too-low prices that allowed only a few producers to stay active. Recent restarts by many companies have revealed only delays, missed production, economic and geopolitical difficulties. In this context, the Dasa project stands out for its quality. It is the largest greenfield uranium project in Africa, with the highest uranium concentration in the continent, and ranks among the best projects under development globally. For American utilities, Global Atomic represents a strategic opportunity to secure a reliable high quality supply—not

only valuable today but even more so in the future. With the new U.S. administration, nuclear has become an energy priority, and securing access to critical raw materials is a central goal. Russia and China have acted in advance, securing control over large portions of global production via Kazatomprom.

Within the African context, the DFC therefore has the opportunity to become the instrument through which the United States can counter Chinese influence (via the Belt and Road Initiative) and Russian influence (name of initiative to be verified). Alongside the fund’s new mission, the appointment of new CEO Benjamin Black could accelerate approval of high-risk but strategic projects like Dasa, aligned with the American geopolitical vision of securing key resources to maintain global

hegemony and counter competitor powers’ programs. In the article “How to DOGE USAID” by Joe Lomsdale and Benjamin Black, it is written: “The DFC’s mandate is to

align development spending with strategic interests and increase accountability, a truly bipartisan goal. The DFC has authority to invest directly in projects across the capital structure, allowing it to respond to coercive strategies like China’s Belt and Road Initiative.”

Also in Bloomberg’s June 10, 2025 article, Black’s idea is presented: “taking more equity risk should be instrumental to the agency as it works more closely with the private Sector”. It is clear therefore that the new CEO will bring a breath of fresh air in favor of project approval.

JV OR ROYALTIES AS ALTERNATIVES?

In a scenario of strong financial pressure and temporary negotiating disadvantage, it is plausible that third parties might seize the opportunity to enter the company’s equity or negotiate royalty-based agreements . Weak market capitalization and urgent funding needs indeed increase the attractiveness of strategic entry by actors willing

to assume risk in exchange for direct exposure to medium-long-term upside potential, taking advantage of a favorable negotiating position amid current circumstances.

Moreover, unlike an institutional lender such as the DFC, a partner acquiring equity or future sales-linked cash flows (via royalties) would have significantly greater leverage on intrinsic project value growth—directly benefiting from future profit expansion and asset appreciation.

In that sense, it cannot be excluded that a Chinese partner—in line with current strategic directions related to critical supply-chain security—might step forward; on the other hand, the likelihood of involvement by Western operators is rising.

Among circulating hypotheses, Uranium Royalty Corp has been mentioned, following its recent proposal of a USD 150 million equity raise. However, just like the unconfirmed idea that the project has already received DFC approval without any announcement from the DFC, this remains speculation until concrete evidence emerges.

Clearly, in any case, we are approaching a crucial turning point: production is expected in Q2 2026, construction is advancing at a pace unmatched among development-stage projects, and any partner entry—public or private—will necessarily need to materialize within the current year.

Beyond this window, further deterioration of the company’s financial position could compromise its ability to raise capital via equity, aggravating its negotiating position and narrowing available options.

IMMEDIATE CAPITAL IN CASE OF LONG-TERM FINANCING APPROVAL?

Recent statements by CEO Stephen Roman have clarified that, at present, there are no active negotiations for immediate capital infusion. However, this possibility could reemerge if an agreement is formalized with the DFC, with an industrial partner via joint venture, or with a financial operator through royalty agreements. Any of these options would require non-negligible technical timelines before generating liquidity, making it nonetheless necessary to raise immediate capital to support the progression of mine construction in the meantime. Once the market gains certainty about financing, the company could more easily unlock bridge financing—expensive and

to be used strategically—and attract off-take agreements from utilities interested in securing future supply through pre-payment arrangements. At the moment, however, such a scenario does not appear feasible. In the absence of concrete short-term developments, it is highly probable the company will need to return to the equity market, via increasingly dilutive—and scarcely sustainable—capital raises.

A STRONG AND RARE INTERNAL DRIVE

Finally, and importantly, one must underscore Steven Roman’s almost visceral passion: he experiences this complex situation with powerful resilience.

In the mining sector—and even more so in uranium—transparency is rare, and it is not unusual for management’s interests to diverge from those of shareholders, with projects pursued more to guarantee internal returns than to generate real value for investors.

Stephen, however, is one of the largest individual shareholders of the company and is fighting with all his strength to see the Dasa project become operational and maximise shareholders return. Certainly, he has made mistakes, but the alignment of positive factors gives hope that the light at the end of the tunnel may not be so far away.

CONCLUSIONS

Ultimately, Global Atomic today stands at a crucial crossroads, suspended between immense challenges and unprecedented opportunity. The complexity of the geopolitical context, financial pressure, and regional instability make this undertaking far from risk-free—but it is precisely in such conditions that the most extraordinary opportunities emerge. Those choosing to believe in the Dasa project are not simply investing in a mine: they are investing in a piece of the global energy future, in a contest between geopolitical giants, in a market where uranium demand is poised to rise sharply in the years ahead. The stakes are high, and the potential return for those able to navigate this unstable terrain could be equally great.

Global Atomic is not an easy or guaranteed promise: it is a formidable challenge, for few chosen ones, requiring vision, patience, and steady nerve. But if the current trajectory is confirmed and critical issues resolve, we could be facing one of the most significant and strategic investments in the global mining landscape.

In this fragile balance between risk and reward, between political uncertainty and potential energy revolutions, only those with the courage to look beyond will grasp the true scale of this opportunity.

Sign up to our free monthly newsletter to recieve the latest on our interviews and articles.

By subscribing you agree to receive our newest articles and interviews and agree with our Privacy Policy.

You may unsubscribe at any time.

We use cookies to improve your experience on our site. By using our site, you consent to cookies.

Websites store cookies to enhance functionality and personalise your experience. You can manage your preferences, but blocking some cookies may impact site performance and services.

Essential cookies enable basic functions and are necessary for the proper function of the website.

These cookies are needed for adding comments on this website.

Statistics cookies collect information anonymously. This information helps us understand how visitors use our website.

Google Analytics is a powerful tool that tracks and analyzes website traffic for informed marketing decisions.

Service URL: policies.google.com

You can find more information in our Privacy Policy.